It isn’t as difficult as you think.

Yes, that’s oversimplifying it. People are usually resistant to change. When confronted with a scenario where they are forced to adapt to something new, decisions aren’t always driven by logic. Emotions take center stage. People worry more about negative performance reviews, being given the boot, engaging a learning curve that makes them feel vulnerable or being demoted to a lesser role. And then there’s the issue of getting stakeholders on the same page which calls for a different ball game altogether.

Managing change stories that hit the target

Accounts and stories I’ve come across are thrilling to read even for leaders who are not change geeks like me. Take the story of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Based in Boston, Massachusetts, the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) was formed through a merger of two hospitals in 1996 (the Beth Israel Hospital which was founded in 1916, and the New England Deaconess Hospital which was founded in 1896). It is now known as a teaching hospital of the Harvard Medical School.

The merger’s main objective was to form a larger hospital (over 600 beds) that would be able to compete with the Birgham Women’s Hospital and the Massachusetts General Hospital.

The two hospitals had different cultures. Beth Israel’s work culture encouraged professional autonomy and creativity. They had always valued a casual management style. New England, on the other hand, was known for its hard-core, rule-based, top-down approach to management.

Loyalty clashes

Staff was hard-core loyal to their own. After the merger, the Beth Israel culture overshadowed New England’s. Those who couldn’t cope (mostly nurses), left to work for competitor hospitals.

By the year 2002, BIDMC was losing up to $100 million a year. They were on the verge of a financial meltdown. Problems with the safety of care and quality were beginning to pop up. The low morale was compounded even more by the deteriorating relationship between the clinical staff and management. Media attention only worsened BIDMC’s reputation.

Consultants to the rescue

External management consultants were immediately brought in. They recommended drastic measures to turn finances around. In 2002, Paul Levy was appointed chief executive officer.

While he had no healthcare background and little knowledge of hospitals, Paul Levy felt that this gave him an edge. As an “outsider” he was a “straight talker” who could act as an honest broker.

The staff of course was skeptical.

Levy’s strategy was based on TRANSPARENCY and COMMITMENT to quality. His first action was to disclose the full scale of financial difficulties to all the staff. He created what he would call a “burning platform” – a scenario escapable only via radical change. His second action was an absolute commitment to continuous improvement of quality. His objective was to build TRUST and establish a sense of common purpose.

When asked to describe his management style, Levy admits that he had an overly developed sense of confidence. But his management approach encourages people to WANT to do well and to WANT to do good. “I create an appropriate environment. I TRUST people. When people make mistakes, it isn’t incompetence. It’s insufficient training or the wrong environment.”

Levy’s Leverage

His strategies were applied in three phases.

Phase 1:

To alleviate the financial burden, Levy decided to let go of people. Save for the nurses, hundreds had to go.

Phase 2:

To improve the poor relationship between medical staff and management, Levy hired Michael Epstein in 2003 as chief operating officer. Epstein, a doctor, met with each clinical department to win their support for the hospital’s non-clinical objectives. His goal was to break down tribalism.

The director for performance assessment and regulatory compliance, Kathleen Murray, joined BIDMC in 2002. Prior, the hospital had no annual operating plans. She began with two departments (orthopedics and surgery) that had volunteered in phase 1. Other departments soon joined. Her operating plans had four goals in mind: 1 – addressing quality and safety, 2 – patient satisfaction, 3 – finance, and 4 – staff and referrer satisfaction. The bigger goal was to make the staff proud of the outcomes and create a sense of achievement. The big change here was doctors’ performance would now be closely monitored. Surprisingly, the introduction of operating plans was seen as a welcome and major turning point.

Phase 3:

While medical errors are inevitable, they had to put measures in place to whittle down incidents. Levy appointed Mark Zeidel as the chief of medicine. Zeidel then introduced measures that cut “central line infection” rates. This reduced both financial costs and harm to patients. It also provided the much need motivation for more improvements.

The board of directors wasn’t too happy with Levy’s suggestion that performance data be published but Levy was quite persuasive. He would publish this information in his blog (an initiative he began in 2006) – which quickly became popular with staff, the public, and the media. Back then, 10,000 visitors a day was huge traffic.

Levy explained that transparency was key. People like to see how they compare with others. They also want to see improvements. For clinical leaders, patients, and insurers, being transparent cannot be overemphasized. As a result, they began to get encouraging feedback from patients. They also managed to avoid a major controversy with the media despite their directness.

Most importantly, what this created was what Levy would call “creative tension within hospitals” so that they hold themselves accountable. This accountability is what drives doctors, nurses, medical staff, and administrators to seek constant improvements in the quality of patient care and the safety of patients. Other initiatives Levy implemented included hiring staff with expertise in lean methods. Training in quality and safety was now mandatory for trainee doctors who had to take part in improvement projects.

Collaboration emerged

In no time, the culture became COLLABORATIVE. Nurses had the respect of doctors and more patients were opting for BIDMC for the quality of nursing care. Departmental quality improvement directors met twice a month to share experiences. Discussion of adverse events was no longer shunned.

By 2010, BIDMC had 6,000 employees. It was a leading academic health center in the United States with state-of-the-art clinical care, teaching, and research. Annual revenues were now over $1.2 billion.

Happy endings

This story had a happy ending, but I could imagine the in-betweens. Organizational change is often problematic. This short narration doesn’t reveal backstories, the nitty gritty, or the happenings in and out of the corridor. You could imagine how challenging it was to persuade people to accept new ways of thinking that could possibly make their skills, knowledge, and working practices obsolete — or how people will react to new roles, relationships, or dynamics.

Does change really need to be that difficult?

My answer to that is… only if change isn’t well managed and lacks employee input and empowerment.

According to a study by Keller and Aiken, (2008, Burnes, 2011 and Rafferty et all, 2013), most estimates put the failure rate of planned changes at around 60% to 70%. In a global survey of 2,000 executives by the consulting company, McKinsey, only 26% of respondents said that their transformational changes had successfully improved performance and enabled the organization to sustain further improvements.

How then do you improve the outcome for your organization?

In our story, you may recall that the hospital was a merger of two organizations with vastly different cultures. The dominating culture was the one with a casual management style, one that also pushed for professional autonomy and creativity.

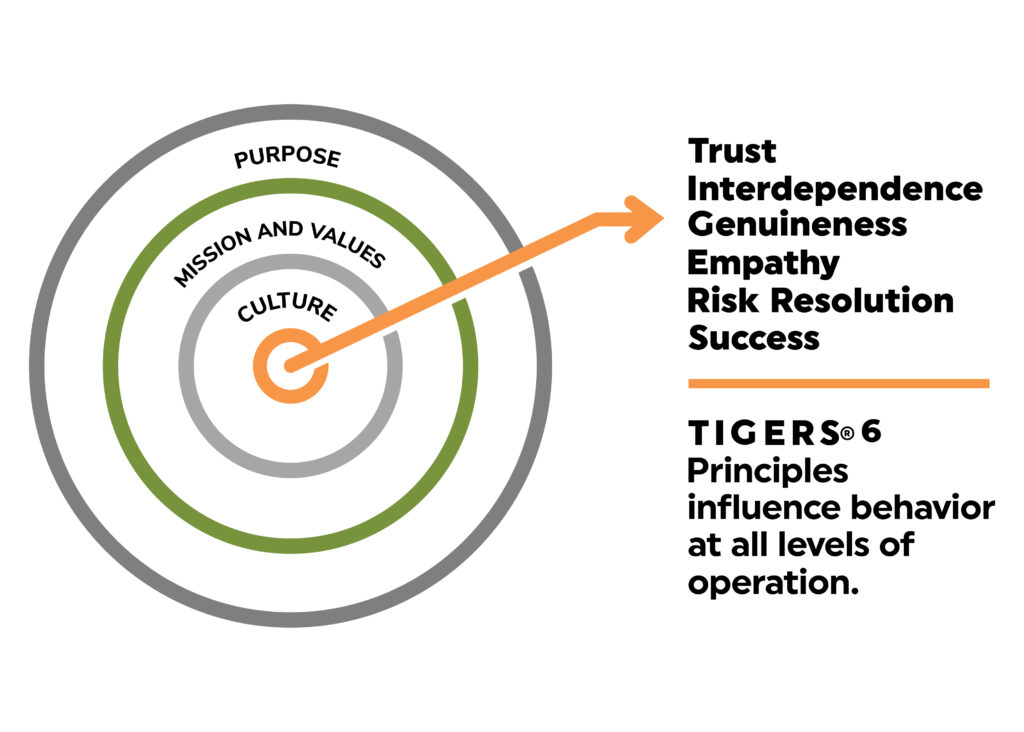

This alone is a huge green light. When a work culture encourages professional autonomy, empowerment and creativity, it says a lot about TRUST, the first of the TIGERS 6 Principles. When there is trust, the organization is likely more open to change. In a huge sense, employees are will be more “agile” and responsive. A top-down approach, on the other hand, means that change will be slow (if it happens at all). Anything new needs due process and committee cycles.

Trained change managers are key

Another aspect that stands out is the importance of a change leader. Change managers are pictured as champions and deviants. Often they are senior managers with considerable power and prestige. Paul Levy spurred change, but so did several managers under his care.

Look closely and you’ll see that real change begins from the middle. Research has consistently demonstrated the key role that middle managers play in organizational change and change management.

- Gathering information

- Championing and justifying alternatives

- Facilitating adaptability by relaxing rules and “buying time”

- Turning goals into action and promoting initiatives to staff

- Facilitating accountable decision-making and planning teams

Middle managers are key to change implementation precisely because they understand frontline operations and issues much better than senior management. They are therefore able to mediate between the top team and the front line. They are best able to identify and promote the need for change.

Change management, of course, can be found at all levels of an organization but providing your managers with the right tools to effect change as effectively (and as painlessly) as possible certainly makes a difference.

Nobody has to suffer when managing change

With the TIGERS principle, we teach your leaders to:

- View situations from different perspectives

- Pinpoint and identify what needs to change

- Facilitate decision-making sessions for optimal accountability and follow-through into change planning and execution

- Use positive and engaging language

- Be open to honest feedback

- Exercise power with courage

- Think and work outside the existing system

On a side note, a concern I come across when consulting to equip leaders for change management is how to select change managers. While I advocate for all managers to have access to this type of training, sometimes I (as an outsider and therefore, an objective party) am asked to make my pick.

I, however, encourage unusual choices. The only thing I keep in mind is this – the senior portion of the organizational chart isn’t the only place to find excellent change managers. There are champions on every level. In many instances, you may even need an outsider like Paul Levy to effect change. Or you might not even require a C-suite leader like him.

Take for instance hidden influencers. Informal influencers are those to whom other team members or staff turn for advice because they have a major impact on attitudes. Retail cashiers have considerable influence because they connect with people daily. It’s case-to-case for every organization. But it’s worth mentioning here that hunting for change managers and influencers involves a good understanding of both the formal and informal networks.

Meanwhile, back to the story

Returning to our story… the BIDMC had a happy ending. But I can imagine how tough Levy had to be.

I could picture the dagger looks, deadly side glances, and even the plot rumor-mongering behind closed doors.

“Do change managers have to be monsters?” Is being a tough, ruthless manager a condition sine qua non for driving change at any cost?

Management always makes difficult decisions whether it’s in the interest of shareholders, stakeholders or the company. Like Levy, this means having to fire, pass over, demote, or fire perfectly decent human beings (some are even well-loved in the organization!). Imagine the horror and the sentiment.

This is why I also offer Genuine Communicator training in the mix of training available to HR leaders who license our platform and leadership training programs for their staff development goals. Change managers have to be comfortable with and able to handle conflict as well as respectfully sincere, frank and forthright communication.

Care to dig deeper into this conversation?

- A good article that explains learning circles for training transference can be found here: A system approach to training that sticks

- Complimentary 30 minute on demand webinar on the TIGERS 6 Principles

- Turnkey training with repeatable resources and templates for coaches, consultants and managers for facilitating conversations with groups of employees on the behaviors that build effective teams and the behaviors that cause predictable problems.

Copyright TIGERS Success Series, Inc. by Dianne Crampton

The TIGERS 6 Principles empower Executives and Consultants with a comprehensive collaborative work culture and leadership system to resolve avoidable talent, engagement and work community problems that stunt growth.

A researched and validated collaborative work culture and facilitative leadership model, licensing is available for HR Executives, Operations and Project Managers, Consultants and Coaches to improve their operations and client success.

Schedule a call to secure a tour of the comprehensive TIGERS 6 Principles system.

Want more tips like these? Receive our newsletter to have insights delivered right to your mailbox.